African Life – June 1963

East African Girls Take Wings

Story by Jill Donisthorpe Pictures: S. K. Gajree

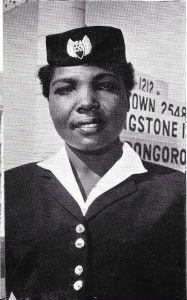

The first African girls to train as air stewardesses for East African Airways have just completed their course at Nairobi Airport. Now they are flying on the scheduled air routes, gaining experience as assistants to fully-fledged stewards and stewardesses. Two of the African girls are already fully qualified after “in-flight” training and have received their “wings”.

Although African men have been working as stewards on this air line for some time now, it was only in October, 1961, that the first African girls were recruited by East African Airways, along with a number of European and Asian girls.

Competition for such jobs among girls of all races in East Africa today is no less fierce than it is in Britain or the United States, but of course relatively few posts are available here.

Fifty-five girls, mainly Europeans and Asians, are at present flying with East African Airways. Turnover is high. On an average, girls leave after two years to get married, which means that about 25 new recruits are needed each year. These replacements are usually trained in small groups of six to ten, but with expansion of services larger numbers are needed. On the last course there were 22 girls, seven of them Africans.

The qualifications required of an airline stewardess are flexible, depending on a combination of personality, education and appearance. Girls must preferably be between 21 and 27, able to speak fluent English, with a School Certificate standard of education. Extra languages are an asset, so is a knowledge of catering, first aid or nursing. Girls have to be of medium build, attractive appearance and personality and are expected to be good “mixers”.

A would-be stewardess is judged first by her letter of application. If this is good, she is asked to fill in a form and send a photograph, after which she is put on the waiting list. When the time comes to select trainees for the next course, applicants are called for a preliminary interview with the Cabin Services Manager, Mr. D. J. Moravec. Much depends on this interview. Many girls throw away their chances at this stage because they give purely frivolous reasons for wanting to fly; many have false ideas about the glamour of the job and are unprepared for the hard work and responsibility.

to be trained as an air stewardess

After the interview, promising candidates are put on a short list and final selection is made by a board consisting of the Cabin Services Manager, the Chief Stewardess and the Establishments Officer. At this stage, special consideration is given to appearance, speech and the confidence which an applicant may inspire. Of the original applicants, perhaps only one in 20 will be accepted for training.

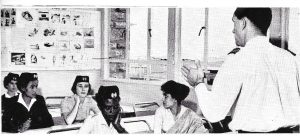

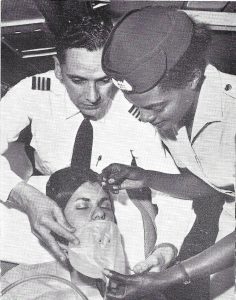

Their ground course, depending on aptitude, can last up to six months, during which the girls learn how to prepare meals and serve drinks and how to approach passengers. They study first aid and midwifery. Immigration, Customs and currency regulations must be learnt and both aircraft and passenger documents understood. Emergency drill is an important part of the training.

International law requires the stewardess to hold a certificate covering every type of aircraft she flies in, and a check must be made every six months.

Training flights are given during this ground training period, and here, perhaps, one or two girls who cannot overcome air sickness may have to drop out. When ground training is finished, and examinations passed, in-flight training begins in earnest. Girls are put on the duty roster, flying regularly under the supervision of experienced staff. The trainee starts on internal flights and gradually progresses to the longer overseas routes. Speed of promotion depends on the individual, but the ambition of each trainee is to get her wings as soon as possible and two of the African girls have already done so. After gaining wings girls can rise from Stewardess Grade III to Stewardess Grade I at the top.

Uniforms are provided—a smart navy suit for ‘winter’ and a light blue linen dress for tropical wear. Asian stewardesses on the Aden—Karachi—Bombay route wear blue and gold saris.

East African Airways’ stewardesses represent, particularly to foreign visitors, not only the national airline, but also East Africa—an area which has high hopes of putting tourism at the head of its list of national assets. So the trainees must try to learn as much as possible about East Africa’s tourist attractions, as well as elementary statistics on population, distances and heights of mountains and airfields.

This year East African Airways expects to carry on all routes, some 200,000 passengers. Probably 150,000 meals and 250,000 refreshment services will be provided by a total cabin staff of 90 stewards and stewardesses.

to colleague Darshi Guram, acting the

part of a Comet passenger.

When she is not serving meals, a stewardess is briefing passengers, answering questions, preparing meals, arranging trays, washing up or paying extra attention to young children, invalids, elderly people and mothers with babies—at almost any hour of the day or night. It is an exacting job but a rewarding one, and the girl who does it well has the satisfaction of knowing that she is making a good impression, not only for herself and her airline, but for her country.